Viveros is really interesting. His works are clearly in part influenced by pin ups, but they aren't pin ups in any traditional sense. There is none of the flirtatiousness or the cute, "Oops! Am I revealing myself in a sexy way?," of the Gil Elvgren school of the pin up, whose work defines most of the era of the classic pin up.

One might be tempted to call them images of femme fatales, due to their sexuality, but they aren't that either. They generally don't call to us (though the above image may be an exception to that rule), nor do they present a clear image of someone with the desire to seduce and destroy. They are simply making us aware of their presence.

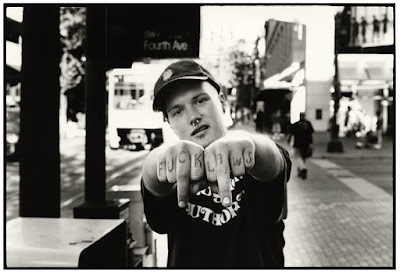

He often mixes female sexuality with uniforms that are associated with male aggression and brutality (the soldier, the matador, the boxer). He likes these women to have blood on them (I am especially fond of the blood on the above image's hands). He also likes to include markers of endurance and experience that are usually associated with men, wounds and bruises. The blood on these women is both someone else's and their own. However, they don't look like victims of violence. They look like participants. Like men with scars, they look like women who can endure.

This isn't typical of the two schools of appropriating masculine forms of dress for female figures. He is not doing the girl with bedhead in her man's button down shirt, nor is he doing Madonna or Demi Moore appropriating business attire and shoulder pads to ape civilized masculine power. These aren't images of women especially connected to men (besides in their uniform and association with violence), nor are they feminist. If they are "empowered," the model being used here does not fit the definition of female empowerment typical of feminist philosophy, associated as their uniforms are with working men (the matador, the soldier, the boxer), not powerful white collar men.

I, of course, like the trademark Viveros cigarette, emblematic these days of the dirtiest and most unacceptable kind of rebellion, since even counterculture often rejects these seemingly former markers of cool. They are emblems of self destruction, though self destruction taken on knowingly and confidently in this case (some of his paintings include a cigarette pack whose brand is apparently called simply, "Fuck It").

He rarely does full body images, mostly face and shoulders, which is interesting since this is the way to distinguish 1940s era pin ups (full body) from glamour girl images (face and shoulders) of the same era. Glamorous women (starlets of the era) were painted face and shoulders only for the most part for magazines and often for poster art, while the calendar girl was featured as a full body painting (Monroe, Bardot, and the like may be the bridge between the two worlds, whose publicity photos often included both types of shots).

They are probably also related to tattoo art, especially as it used to more often define the lower class. These women, perhaps, have more in common with the trailer park, the biker chick, the 1980s stoner girl in a Def Leppard t-shirt.

I have no particular thesis here. Still thinking about them more than anything else within these clear contexts that Viveros is drawing from, but is also upending.

Additional works by Viveros and a brief discussion of the ubiquity of the cigarette in his work